The Church and Dwight Art Collection - A Bit of Background

In late 2024, Flux was contacted by the Arts Council of Princeton about a collection of paintings owned by Church & Dwight Co., Inc., the makers of Arm & Hammer Baking Soda. The collection of paintings, thirty in total, played a large role in the company’s history, particularly its early marketing campaigns.

Brief History of Church & Dwight Co, Inc.

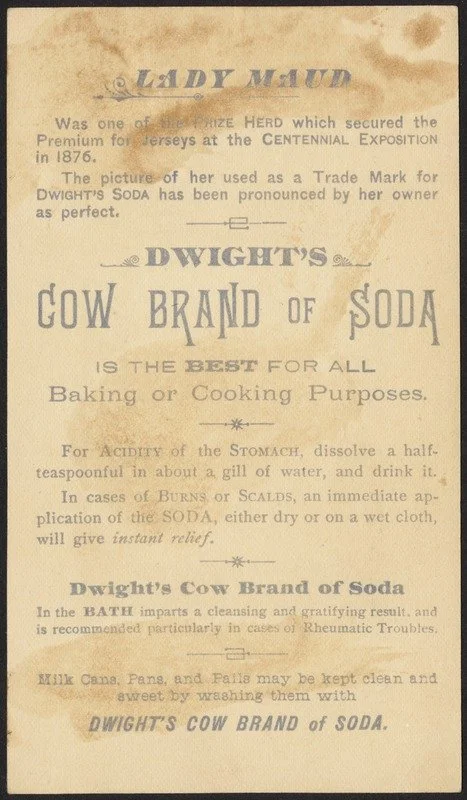

First, let’s start with some background on Church & Dwight Co, Inc. The company’s story begins in 1846 when brothers-in-law John Dwight and Dr. Austin Church began packaging baking soda in Dwight’s kitchen and selling it to customers under the name John Dwight and Company. In 1867, Church retired, and his sons formed a separate company they called Church & Co., which sold baking soda under the brand name Arm & Hammer, using the famous logo of an arm holding a hammer from the start. In 1876, Dwight changed his company name and logo again to differentiate his baking soda from his nephews’ brand. Dwight’s Cow Brand Saleratus featured a cow as their logo, chosen because of the popularity of using baking soda mixed with sour milk in recipes at the time. Fun fact! Dwight didn’t just use a random drawing of a cow for his logo, he used a specific cow - Lady Maud, a prize-winning cow at the Philadelphia Centennial Expedition.

After almost 30 years of friendly competition, Church & Co. And John Dwight and Company merged in 1896 to form Church & Dwight Co., Inc. The new company continued to produce both Arm & Hammer Baking Soda and Dwight’s Cow Brand Saleratus, or as it was more popularly known, the Cow Brand, until 1965 when it consolidated the brands under the Arm & Hammer name.

Church & Dwight Co. Trading Cards

Now, onto the paintings. What role could these thirty paintings have played in the history of Church & Dwight Co., Inc. and the marketing of baking soda? Beginning in the mid-late 1800s, it became popular for companies to give away small, illustrated cards with the purchase of their products. The cards were either packaged with the product or given to customers by the store clerk. You have probably heard about the baseball cards and other trading cards that kids used to get from packs of gum and, later, cereal boxes. The trading cards from the 1800s were distributed in the same manner but were first found in packs of cigarettes and focused on topics geared towards adult men, the main customer base for cigarette companies. When other companies saw how popular the trading cards in cigarette packs were, they jumped on board the trend. And so, in 1888, Church & Co.’s Arm & Hammer Baking Soda released its first series of trading cards: “Beautiful Birds of America.” The set consisted of sixty cards with each card featuring a different bird. Each card had an image of the bird on the front with a short, informative blurb about the bird and the importance of preserving nature on the back, in addition to an ad for Arm & Hammer Baking Soda and how you could purchase a complete set of the trading cards by writing a letter to Church & Co. that included a small payment and a self-addressed envelope. The preservation and protection of nature, and birds in particular, was a cause that the company leaders firmly believed in. The original series was an immediate hit! This led to the distribution of 22 other trading card series over the years produced for either Arm & Hammer Baking Soda, Dwight’s Cow Brand Saleratus, or both brands. The trading card series mostly featured different North American birds, but there were also series featuring dogs, wild animals, plants, and even nursery rhyme characters. And, of course, the Cow Brand had a series of cow cards, because how could they not? All of the cards were known and desired, both then and now, for the beautiful illustrations found on the front.

Depending on the series, there were either 15, 30, or 60 cards in total to make a complete set. The various trading card series were re-released numerous times over the years, with the regular distribution ending in 1966. This led to multiple variations of the series, with differences in the sizes of the cards and the text printed on the back. A final commemorative set was published in 1976, called Birds of Prey. The set consisted of ten cards featuring images of various raptors that had never been printed in any of the previous series. Overall, 6,232 different trading cards were printed and distributed by Church & Dwight Co., Inc. when all the series and their multiple releases and variations are taken into account.

Background on the Paintings

The paintings we are treating in the studio are the original, commissioned artworks by well-known painters and illustrators of the time upon which the card illustrations are based. After opening all thirty paintings, we learned that the paintings sent to us for restoration all feature either birds or dogs and represent four different trading card series originally released between 1902 and 1910. All thirty paintings were painted by either John Henry Hintermeister or Gustav Muss-Arnolt, with Hintermeister painting four of the bird paintings and Muss-Arnolt painting all twenty-one of the dog paintings and the remaining five bird paintings.

John Henry Hintermeister’s four bird paintings belong to the 1908 New Series of Birds set. It was the fourth series of bird trading cards released by the company, and it consisted of thirty cards in total. Four of Gustav Muss-Arnolt's bird paintings belong to the 1904 Game Bird Series set. It was the third series of bird trading cards released by the company, and it consisted of thirty cards in total. His last bird painting belongs to the 1908 New Series of Birds set previously mentioned. Muss-Arnolt's dog paintings belong to either the 1902 Champion Dog Series set or the 1910 New Series of Dogs set. These were the only two sets of cards featuring dogs, and they were only branded for and distributed in Dwight’s Cow Brand Saleratus boxes. Both sets had thirty cards in total.

From Painting to Trading Card

The question not yet answered is “How do you go from a 9 x 12-inch painting on canvas to a 2 x 3-inch card printed on paper?” We believe the printed cards are chromolithographs. Chromolithography is the process of creating a colored print via the lithographic printing process. Lithography is all about how grease and water mix - or don’t mix in this case - on a special lithographic stone, usually a specific kind of limestone from the area of Bavaria in Germany. Lithographers start with a blank lithographic stone upon which they draw the image they want to print using a lithographic crayon, pencil, or chalk. The lithographic crayons, pencils, and chalks are made from a greasy, fatty soap that will eventually repel water and act as a surface the greasy lithographic ink will adhere too, while the blank spaces on the lithographic stone, after a special processing and etching process, will absorb water and repel the lithographic ink. That is a very quick explanation of the general process. For a much better explanation of lithography with visuals, check out Pressure + Ink: Lithography Process, a video from the Museum of Modern Art where Phil Sanders, the Director of the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, walks you through the whole process. In order to create a chromolithograph, multiple lithographic stones needed to be created, one for each color to be used.

When a lithographer is given a painting to turn into a print, the first step is to trace the painting and all of its details onto a separate piece of paper, creating an outline of the painting and the details, called a keyline drawing, that served as a color map. In the case of the Church & Dwight paintings, the lithographer most likely also had to do some further translation of the outlines to shrink the original drawing down to the desired final size of 2 x 3 inches. This keyline drawing is transferred onto the lithographic stone using tracing paper and iron oxide, and the outlines would be then drawn onto the stone with a lithographic crayon, pencil, or chalk. This stone served as a proof stone. Next the lithographer would analyze the painting, noting the various colors and tones used throughout, and decide how many colors need to be used to replicate the colors and tones found in the painting. In the video, How to Make a Colored Lithograph, from the Van Gogh Museum, master printmaker Christian Bramsen describes himself as not just a printer, but a colorist, because he has to be able to figure out just the right colors to use and how they will interact to create the final, desired effect. Once the number of colors is decided upon, the lithographer knows how many stones need to be created. The keyline drawing is again transferred onto the required number of stones, and the lithographer would proceed to draw and fill in different, specific outlined shapes and elements as necessary on all the stones, depending on the color ink to be used on that stone. Each stone would then undergo processing and etching to prepare it for ink and printing. From there the first stone would be inked, set in the press, and the first layer and color of ink was printed onto the paper. This process was repeated for all of the lithographic stones and colors needed until the paper was finally pressed onto the last stone with the last color. In order to ensure that every pass through the printing press lined up with the previous one, printers use a system called registration, where they create identical marks on every lithographic stone being used and all pieces of paper to be printed that they then line up precisely for each pass. If the registration is off and not aligned properly, the printed image will be blurry and the colors will not “mix” properly.

Once again, this brief description does not do justice to the whole process and the amount of skill, time, and work that would go into these prints. We were lucky to find a thorough explanation, with visuals, of making a chromolithograph produced as a book in 1888 by L. Prang & Co., one of the premier lithography shops in the United States at the time that was owned by one of the premier chromolithographers in the world, Louis Prang. The book, Prang’s Prize Babies. How this Picture is Made is a progressive proof book that shows how nineteen different lithographic stones were used to create the chromolithograph known as Prang’s Prize Babies, which was based on an oil painting by the artist Ida Waugh. It starts with the original keyline proof print and then walks you through each successive stone, showing how each individual printed color looks alone and then combined with all the previously printed colors before it, so you can see how the colors build upon each other to truly capture and recreate all of the colors, tones, and hues found in the original oil painting. Although we do not know for sure what lithograph shop Church & Dwight Co., Inc. hired to print their trade cards, there is evidence that they may have used Forbes Lithograph Manufacturing Company based on labels on the back of some paintings. Either way, this is the process the lithographer would have followed to capture all of the details and the colors, tones, and hues both Muss-Arnolt and Hintermeister chose to expertly capture the beauty of the birds and dogs they painted.

As previously mentioned, the trading cards were very popular at the time. To build on the trading cards popularity, Church & Dwight Co., Inc. released other promotional products that used the images from the trading cards. There were numerous items merchants could display to advertise the two different baking soda brands and the current set of cards available such as display cards and window signs. Church & Dwight Co., Inc. released calendars in the 1920s that featured the bird pictures for the general public, and in 1938 they created and distributed posters titled “Birds: Nature’s Protectors.” In addition to featuring images from the “Beautiful Birds of America” series, the posters presented information on how birds help to protect crops and nature to help promote efforts to protect birds and conserve the environment. There was even a guide on the back to help teachers include environmental conservation and protection of birds in their lesson plans and discuss the topics with their students. Today, the trading cards are collectible items that can be found and purchased in antique stores and auctions. The trading cards appeal to collectors of ephemera in general, those who specifically collect vintage advertising memorabilia, and those who only collect non-sport trading cards. They also appeal to bird enthusiasts who appreciate the fine artwork and to people who just think the trading cards are neat and pretty. It has been really exciting to have the original paintings for these trading cards in the studio and have the opportunity to learn the history behind them and the important role they played in the history of Church & Dwight Co., Inc.

Bibliography

American Jersey Cattle Club. 1877. Herd Register of the American Jersey Cattle Club. vol. 4, 1876. Published by the Club. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hw2sv2&seq=7. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Arm & Hammer. 2019. “A trusted solution for more than 170 years. Pure and simple.” Arm & Hammer. https://www.armandhammer.com/en/about-us. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Arm & Hammer. 2021. “Our Heritage.” Arm & Hammer. https://www.armandhammer.co.uk/our-heritage/. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Bockrath, Diane. “World in Color: Chromolithography, Advertising Ephemera, & the Visual Landscape with Diane Bockrath.” May 24, 2021. Virtual presentation, posted by Hagley Museum and Library, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wENVatM37vo.

Church & Dwight Co., Inc. 2025. “Our History.” Church & Dwight Co., Inc. https://churchdwight.com/company/history.aspx. (accessed June 26, 2025).

"Dwight's super-carb. soda." Card. [ca. 1870–1900]. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/3b591b119. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Erickson, Laura. 2017. “Arm & Hammer Bird Trading Cards.” Laura Erickson’s For the Birds (blog). July 6, 2017. https://blog.lauraerickson.com/2017/07/arm-hammer-bird-trading-cards.html. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Lill, Joe. 2024. “Soda Cards.” Music by Joe Lill. Last modified June 24. https://www.musicbyjoelill.com/sodacards.htm. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Los Angeles Printmaking Society. “Stone Lithography Demonstration: Etching and Printing a Limestone.” December 8, 2021. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGehTZSEBss.

Some Print Dude. “Hand drawing a CMYK Stone Lithograph.” May 12, 2023. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=75WN9NrY70s.

Some Print Dude. “How to make a 1 Color Stone Lithograph start to finish.” March 20, 2023. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNNgrIejf8s.

Some Print Dude. “Making a Big Stone Lithograph w/ Screen Print Color.” January 20, 2023. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zmwTRB-d2_s.

The Clark. “Hue & Cry: French Printmaking and the Debate Over Colors - Chromolithography.” 2025. https://www.clarkart.edu/microsites/hue-cry/chromolithography. (accessed June 26, 2025).

The Met. “Lithograph.” 2000-2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/printmaking/lithograph. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Wikipedia. 2025. “Arm & Hammer.” Wikipedia. Last modified May 23. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arm_%26_Hammer. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Wikipedia. 2023. “Austin Church.” Wikipedia. Last modified October 9. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austin_Church. (accessed June 26, 2025).

Wikipedia. 2025. “Church & Dwight.” Wikipedia. Last modified May 29. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_%26_Dwight. (accessed June 26, 2025).