Investigating the Life of a Painting

Fig. 1 Master John Homans; c. 1760; Joseph Badger (1708-1765); 28 ½” x 24”; before treatment; normal light; framed

When we walk through a museum, there is a lot we can learn from a painting on a wall. We can learn more about an artist, period, style, or get lost studying the brushwork until the guard tells you to step back. But, there’s so much more to the story that’s rarely told. As a paintings conservator, I get to investigate the life of a painting, uncover old damages, and piece together clues to understand how much has changed since it first left the artist’s studio. The Joseph Badger (1708-1765) painting (fig. 1), Master John Homans (c1760) came to our studio for a large tear through the lower center of the painting. For a painting that has survived 265 years, was this really the first tear?

My investigation started with photography while the painting was still framed. The three-quarter portrait portrays a young John Homans standing in front of a landscape background. He wears a white dress, consistent with mid-18th century children’s attire, and he’s holding a silver bell and coral rattle. This is a typical composition for Joseph Badger, a leading self-trained portrait painter in Boston. Badger used the cool, gray ground as shadows in the sitter’s face and dress where thinner paint applications expose the darker color below.

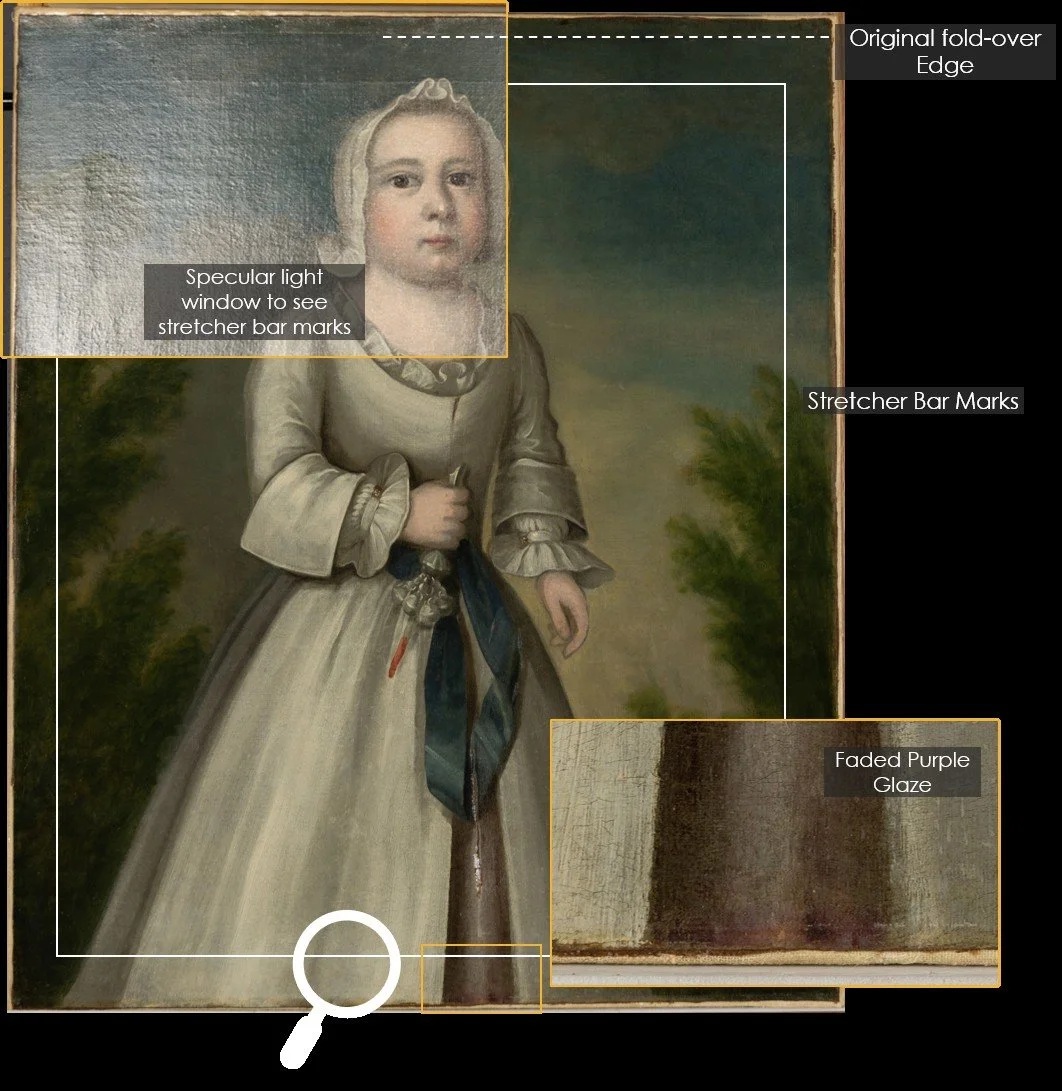

I saw my first clue after we carefully unframed the portrait. Along the bottom edge usually hidden by the frame was a strip of bright purple (fig. 4). It is likely that the petticoat in the center front of the skirt was originally painted with a more vibrant, cool purple glaze that has now faded. Organic lake pigments are prone to fading from light degradation.

When we turned on the ultra violet lights for photography, we could see at least two campaigns of previous retouching (fig. 3). When a painting is as old as Master John Homans, it has already been through the hands of past conservators long before me. It’s been cleaned before, revarnished, repaired, retouched. Retouching, or non-original paint added to conceal a damage, typically appears dark under a UV light. The dark spots can be seen above and below the varnish layer which appears as blue autofluorescence under 365 nm UV. The reverse L-shaped retouching on the middle right side of the image looks suspiciously like an old tear repair.

When we flipped the painting around to photograph the back, it became clear that this could not possibly be what the verso looked like when Badger painted it. The wooden keys at each corner of the support are indicative of an expandable stretcher, a design not patented until the nineteenth century, decades after Badger’s death. The canvas too was suspicious as the lighter fabric tacked to the stretcher bars did not match the rest. My initial examination concluded that the canvas had been edge-lined, which meant strips of new canvas were attached to the edges of the original. This is a common treatment conservators do to reinforce the vulnerable tacking margins and facilitate stretching around the support. In this case, the original canvas around the painting had been trimmed off, a step we would not do today.

Although we no longer have Badger’s original support, I was able to uncover more evidence as to what that looked like after closer inspection of the marks on the paint surface. Stretcher bar marks appear as cracks or dents in the paint where the support comes into repeated contact with the back of the canvas. In this case, there is a border around the painting about 1½-inch in from the edge (fig. 4) which does not correspond to the current stretcher (2¼-inch-wide members). There is an extra horizontal mark running across the top, ½ inch below the edge which suggests this is an earlier turnover edge that was extended during a previous treatment campaign to be part of the composition.

Fig. 4 Diagram noting stretcher bar marks from the original support and faded purple color at the bottom.

When I examined the new tear under magnification, I could see that the tear cut through two layers of canvas - meaning the painting had been through much more than just an edge lining. The original canvas had actually been fully lined to a second piece of linen (fig. 5). This treatment could have been done to repair that L-shaped damage we saw under UV light. The tacking margins on both the original and lining canvases must have been cut down prior to the edge-lining treatment, making it tricky to understand right away that the painting was lined.

Fig 5 Detail of the lower edge noting original, lining, and edge lining canvases

Older damages to the paint layers revealed themselves as I continued to scan the surface under the microscope. There was a fair amount of abrasion throughout which could be indicative of overcleaning in earlier treatment campaigns (fig. 6). It is common practice for yellowed coatings to be cleaned and replaced. Overcleaning can lead to tiny paint losses on the peaks of the canvas weave which was especially true during earlier restorations when conservators were using more aggressive solvent mixtures than what we have available today.

Fig. 6 Photomicrographs highlighting overcleaned paint

The present coating was not severely discolored and the surface only needed a light aqueous cleaning to reduce some grime. Under the microscope, I mended the tear using a flexible and strong material that I could apply with heat to the gap on both the original and lining canvases. Finally, I inpainted the mend to match the surrounding image using reversible conservation paints and I toned some of the older mismatched retouching to match the original.

In the 265 years since Badger painted John Homans, the painting has indeed been through a lot more than one tear. It’s been lined, trimmed, extended, edge lined, and stretched to a modern support. Multiple hands have removed and reapplied varnishes and added paint where it was lost. The next conservator who looks at the surface under a UV light will find evidence for my tear repair too.